GLOSSARY

What is PCIe?

Peripheral Component Interconnect Express (PCIe) is a standardized interconnect for components and peripherals for today’s computers. It allows components like SSDs, graphics cards, and add-in cards to be plugged into any modern motherboard and function properly without requiring proprietary interfaces or non-standard protocols to break things or make installation confusing.

PCI Express was designed to be an industry standard interconnect for components and peripherals to replace the separate interfaces on motherboards in PCs of yore, namely AGP and PCI. Back then we used AGP for graphics card(s), and PCI ports for soundcards, networking cards, RAID controllers, etc. PCI Express replaced all of those interfaces when it was introduced in 2003, and it was designed with plenty of headroom to allow for future advances in bandwidth and performance, so it’s expected to have a very long lifespan. Even today it is still ahead of the curve, but more on that in a little bit.

PCI Express Design

PCI Express is a point-to-point serial interface between devices, with the PCIe device and the CPU and chipset communicating over physical “lanes” built into both ends of the connection. PCIe lanes use two pairs of copper cables per-lane to send data in both directions simultaneously, and the genius of the design is bandwidth can be somewhat easily increased by adding (or using) more lanes. It’s also backwards compatible, so a PCIe 3.0 device works just fine on a PCIe 4.0 system, making it a unique interface with a very flexible design.

Where Do I find PCI Express in My Computer?

PCI Express technology is currently a feature of both CPUs and CPU chipsets from AMD and Intel, so when you look at a spec sheet you’ll see PCI Express support for both of those technologies listed as "number of PCIe lanes." The number of available lanes will vary depending on the CPU and CPU chipset, with flagship products offering more lanes and mainstream products offering fewer lanes.

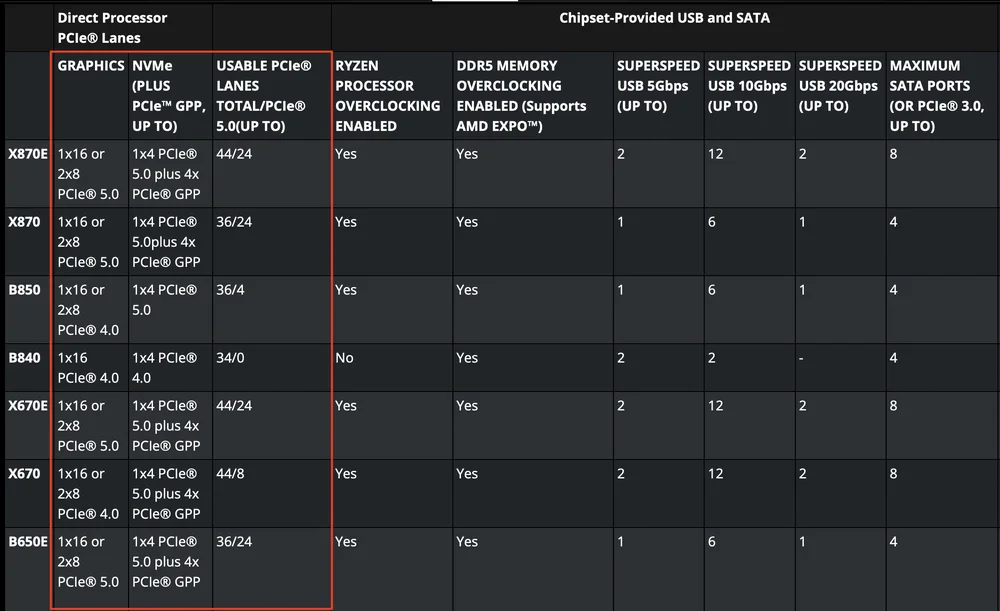

Higher-end chipsets offer more PCIe lanes, as we can see here with AMD's newest chipsets for AM5.

Note that there are PCIe lanes for both the CPU and the chipset, but these lanes are not equal even though all of them ultimately connect to the CPU. The lanes that come from the chipset must connect to the CPU via a DMI link (Direct Media Interface), while the lanes that connect directly to the CPU bypass this middle-man connector. This means that you should be careful to put your GPU and at least primary SSD into the slots that do not use that middle-man connection.

PCI Express Lane Usage

All PCIe devices uses a specific number of lanes, express with a small “x” and a number representing how many lanes it uses. For example, a modern GPU like the RTX 5090 is PCIe 5.0 x16 device, meaning it is using the 5th iteration of the PCI Express standard (PCIe 5.0 or Gen 5) and it utilizes 16 lanes for data transmission, which is the most allowed currently. There are also devices that use 8 lanes (x8), 4 lanes (x4), two lanes (x2), and 1 lane (x1).

There is a penalty for using more lanes, of course, such as added heat generation and power requirements, as there is never a free lunch in computing, but having the ability to use a different number of lanes for data transmission gives hardware manufacturers options when it comes to designing their products.

It can also work in the other direction, where a device could go from x16 to x8 to save power and produce less heat, assuming performance isn’t heavily impacted or that reducing the performance is a worthwhile trade off.

The CORSAIR MP700 Pro is a PCIe 5.0 x4 NVME SSD

Bandwidth Doubles Every Generation

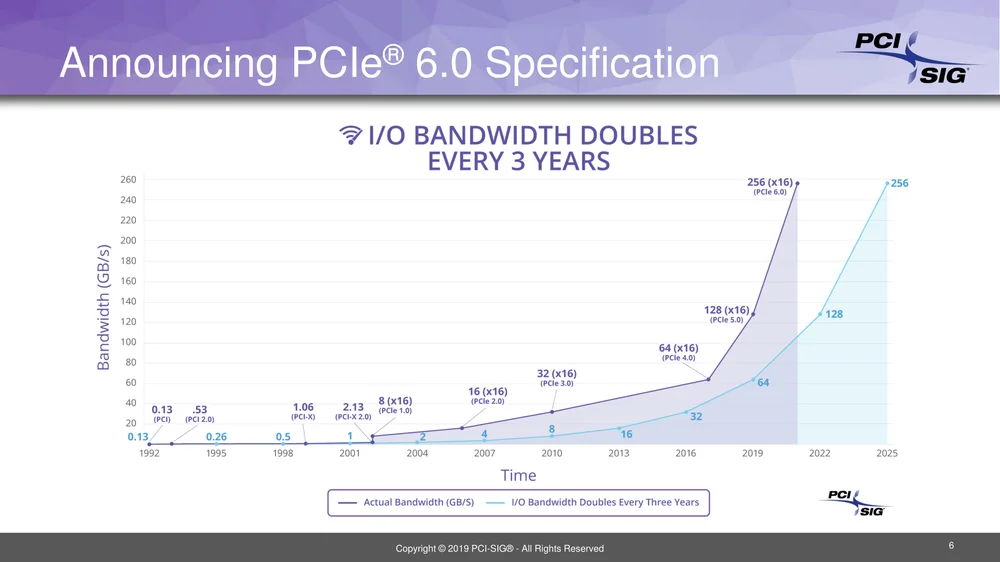

Since its inception PCI Express has been able to double the amount of bandwidth provided by the interface each new generation, which is an astonishing feat. That doubling of bandwidth is expected to continue for the foreseeable future as well, giving all of us PC users something to salivate over while we envision a PCIe 7.0 GPU with quadruple the bandwidth of our current GPUs. Whether or not the GPUs can actually use that much bandwidth is a different story, however.

This chart from PCI-SIG shows how bandwidth doubles every three years with a new version of PCI Express, though each version takes many years to become ubiquitous (not to mention affordable.)

PCIe Bandwidth History

As we noted above, the people behind the PCI Express interface at PCI-SIG have been able to double the bandwidth offered by each new iteration of PCIe Express, which is a trend that is expected to continue far into the future. Here’s how it’s progressed so far:

| Slot Width | PCIe 1.0 (2003) | PCIe 2.0 (2007) | PCIe 3.0 (2010) | PCIe 4.0 (2017) | PCIe 5.0 (2019) | PCIe 6.0 (2021) |

| x1 | 0.25GB/s | 0.5GB/s | 1GB/s | 2GB/s | 4GB/s | 8GB/s |

| x2 | 05GB/s | 1GB/s | 2GB/s | 4GB/s | 8GB/s | 16GB/s |

| x4 | 1GB/s | 2GB/s | 4GB/s | 8GB/s | 16GB/s | 32GB/s |

| x8 | 2GB/s | 4GB/s | 8GB/s | 16GB/s | 32GB/s | 64GB/s |

| x16 | 4GB/s | 8GB/s | 16GB/s | 32GB/s | 64GB/s | 128GB/s |

One thing that is very notable in the above chart is we can identify the long lifespan of each PCIe generation these days. It notes that PCIe 5.0 was introduced in 2019, but here in 2025 it’s still not completely dominant, as most devices still use PCIe 3.0 and 4.0. In fact, Nvidia’s new RTX 50-series are PCIe 5.0 GPUs, but that is a first for the company as its previous Ada Lovelace 40-series cards from 2022 were PCIe 4.0. AMD’s previous generation 7000-series GPUs were also PCIe 4.0, but both companies newest GPUs are finally PCIe 5.0.

At the same time, the chart notes PCIe 6.0 was announced in 2021, but it will be years until that is in the market, and years after that before it’s ubiquitous, which could mean 2030 or so. That would put PCIe 7.0 around 2035, so these standards have a very long lifespan and are introduced way before they are needed in the marketplace.

What Devices Use PCI Express?

In 2025 a PCIe Express device is anything that plugs into the slots on your motherboard below the CPU, which means GPUs and any add-in cards that go into the PCIe slots. This would include USB expansion cards, network cards, RAID controllers, soundcards, and so forth. Note M.2 SSDs are also PCI Express devices, and they have their own dedicated ports on today’s motherboards that are different from expansion slots but fill the same purpose in that they connect to the CPU and chipset for data transfer to the host system.

Do We Really Need all of this Bandwidth?

Just because PCI Express doubles its bandwidth every iteration doesn’t mean there is double performance, and a good example of this phenomenon is the current crop of M.2 SSDs. PCIe 4.0 SSDs have been out for many years and are very common, and they top out at ~7GB/s of bandwidth. On the other hand, PCIe 5.0 drives are newer, and offer up to ~12-14GB/s of bandwidth, which seems like a no-brainer upgrade, but in the real world the actual performance benefit between these two families of drives can be huge or very small, depending on the application.

If you’re using the drive to actually read and write large files repeatedly it can be a massive upgrade, as we noted in our article here. However, if you’re primarily using an SSD for gaming, the difference in game load times will likely be minimal.

The other issue facing PCIe 5.0 SSDs right now is they are more expensive than PCIe 4.0 drives, and also motherboards with PCIe 5.0 SSD M.2 ports are not ubiquitous, but that will change in the next 5 years.

What's Next for PCI Express?

As this is being written in mid-2025 we are all waiting for PCIe 5.0 to become the new standard, but that might take a few years. The latest CPU chipsets from AMD and Intel support PCIe 5.0, and the GPUs from AMD and Nvidia are also PCIe 5.0, so at this point it's expected that all new hardware will support the latest interface, which will help PCIe 5.0 become the new standard. More people will upgrade from PCIe 4.0 to PCIe 5.0 when those devices are the only options available. For example, in the year 2027 if you want to buy a new M.2 SSD, you will likely have to buy a PCIe 5.0 device, similar to how it’s hard to buy DDR4 memory these days since the market has shifted to DDR5.

Therefore, in several years, we might start to see PCIe 6.0 devices roll out, but our guess would be new hardware won't arrive until 2028 or so. Given how long it’s taking for PCIe 5.0 to gain a foothold in the market—more than 6 years—those devices might not be in vogue until the end of the decade.

For what it’s worth, PCI-SIG is already hard at work on the PCIe 7.0 standard as well, so like we wrote above, this is a very forward-looking organization that is always many steps ahead of where the market currently is, which is great news for the PC industry at large.